In this article we examine the evolution of consumers from retail consumers to platform consumers, as businesses move into the ecosystem and marketplaces emerge to manage B2C and peer to peer sales. We observe how platforms have changed customer expectations and behaviours and discuss the impact on businesses, and how their service models have evolved as a result.

Platform marketplace

Platform marketplace

The 21st century has been characterised by many social, economic and technological developments, but nothing has changed the way customers interact with businesses more than the emergence of platform enabled retail. It has changed the way people buy things, the way they shop for things, their expectations and their behaviours. It has also revolutionised aspects of retail that have led to the emergence of platform giants and opened up markets for retailers in completely new ways.

The platform revolution is ongoing. Retailers, producers and customers are moving into the ecosystem economy, supported and led by more sophisticated and more specialised platforms. While it has made significant changes to the way we work, shop and think about consumption already, many more changes are in store. We explore some of the future state changes in other parts of this section.

What’s a platform?

In technical terms, a platform is a technology or set of technologies that supports the running of other technologies. Specifically in the context of marketplace platforms, a platform is a technology that supports the distribution of content from producers to consumers, or between each other (prosumers), without the need for a dedicated retail outlet. They take various forms – we are all familiar with Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, Twitter and other social media platforms, primarily designed for sharing content, and with a business model based on advertising and paid content; others are more obviously dedicated to giving small (and increasingly large) producers access to a wide range of customers, such as ebay and Alibaba. Other platforms are dedicated to specific markets and audiences, such as Uber or AirBnB (rides and rooms) or piecework such as freelancer.com, taskrabbit, or upwork.com.

There are also platforms dedicated to various specialised services, such as payments (PayPal), document sharing (dropbox), petsitting, car sharing, bikes, houses, gardening, you name it… and of course, porn. Spotify and Netflix are the best known media sharing platforms which, like Amazon, both sell on their own behalf (Netflix and Amazon are also production companies) and provide a platform for third parties. Crowdfunding and peer to peer lending platforms are also applications described elsewhere in our articles.

The characteristics of a platform described by Sangeet Paul Choudary in Platform Scale, are three key conceptual layers: a network/marketplace/community layer, which includes the community of consumers, producers, prosumers and their interactions; the infrastructure layer that manages the interactions and the platform availability, and the data layer, where analytics support the effective functioning of the others.

The key differentiator of a marketplace platform is that it supports consumer / producer / prosumer interactions, so other large commercial web systems don’t fall into this category directly, although many large commercial sites do run on some of the big platforms aimed at small and larger businesses, and if you are using a dedicated website for a small business, or even a large one, you may well be interacting with one of these without being aware of it.

A short history of marketplace platforms

The history of online platforms is inextricably linked with the development of two key access facilitators: web browsers and search engines.

The history of online platforms is inextricably linked with the development of two key access facilitators: web browsers and search engines.

Following the development of the World Wide Web, initially for academic purposes, by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, the first cross-platform web browser was developed by fellow English mathematician Nicola Pellow in 1991. Technologists slowly started to realise the potential, and by 1994, a few false start platforms were emerging on the world wide web, hampered by poor bandwidth and limited browser capabilities. The milestone browser Netscape Navigator, launched late in 1994, when Mark Zuckerberg turned 10, started to take hold as Amazon launched in the books market in 1995, alongside e-Bay (originally AuctionWeb).

Netflix started its online DVD service in 1997, the year Larry Page and Sergey Brin were writing their research paper, Amazon went public and Jeff Bezos issued his first famous letter to shareholders. PayPal followed in 1998, while Netscape plummeted from market dominance, as Microsoft pursued an aggressive bundling strategy to get Internet Explorer to market dominance. Thanks to the escalating browser war and growing usage, browsers were improving while infrastructure developments, particularly bandwidth, improved accessibility and usability significantly.

Towards the end of the 1990s, while organisations like the ones we were working within were moving from intranet and flat websites towards building their own functional commercial sites, Amazon, e-Bay, YouTube and Netflix were paving the way for many more enterprising entrepreneurs to identify the opportunity offered by the internet and increasingly user friendly functionality, among them Zappos and the Chinese online marketplace AliBaba. By 2000 most schools and businesses in developed economies had access to some form of broadband access, although most private users were still on dial-up modems, and governments were prioritising public broadband access, recognising the growing importance of the web in people’s lives.

It was then, on the wave of the dot.com boom, that incumbent businesses such as supermarkets and banks started launching their own online sites; Sofie was responsible for one of the first online wealth managers in 2001, while Walmart, Safeway and Costco all started providing online services. Although banks and large retailers had the advantage of infrastructure and existing customer bases, they were slow to learn the lessons from the early platforms, with Amazon in particular capturing a growing market, partly thanks to its 1999 launch of i-Click, allowing faster purchases but also thanks to its growing range of products, culminating in the launch of Amazon Marketplace in 2002, where third party sellers can sell via the platform.

With e-Bay, Amazon Marketplace, AliBaba and a growing range of more specialist B2C platforms emerged, fuelled by the early successes and learning from some early failures. In parallel, the acquisition of PayPal by eBay in 2002 enabled the development of secure payments over peer to peer platforms. This accelerated the development of peer to peer marketplace platforms, enabling small payments to be transferred securely without compromising personal payment details.

AmazonTurk was the first peer to peer service exchange site, launched in 2005, enabling individual producers to sell intelligence based services via a basic marketplace to buyers at a set price. This is also when YouTube, the peer to peer video sharing site, was born, the brainchild of ex-PayPal employees, which rapidly caught on to become one of the fastest growing sites of 2006.

With the release of the iPhone in June 2007 and shortly afterwards, the rival Android phone, platforms for sharing Apps arose, allowing for both distribution of phone-enabled apps by existing companies, and the reshaping of the business model for a large part of the games industry. At the same time, Netflix started offering online streaming for a subscription, alongside Hulu.

With the release of the iPhone in June 2007 and shortly afterwards, the rival Android phone, platforms for sharing Apps arose, allowing for both distribution of phone-enabled apps by existing companies, and the reshaping of the business model for a large part of the games industry. At the same time, Netflix started offering online streaming for a subscription, alongside Hulu.

Since then, many peer to peer marketplaces have been developed, in areas as diverse as education, lending, travel, car sharing, clothes, recreation, venues (we mentioned dog sitting) currency exchange, media and of course the general commerce, and peer to peer service sites.

Founded in 2008, AirBnB was the first marketplace for people to share spaces in their homes, while Uber (2009) was the first to offer rides in people’s cars at scale. Both grew in parallel with the skills sharing sites, which have all had a significant impact on supplier behaviour which we discuss below. Peer to peer lending has changed the dynamics of a certain class of startup business, while peer to peer selling has changed the cost and dynamics of running a retail business. But the biggest impact has been on customer behaviour.

User generated content and social platforms

While selling things is always a prime motivator for developing technology, communication is another basic human need that has always exploited new technology as it became available, and online chat rooms existed before browsers were developed, enabling groups of related people to communicate simultaneously, so the move to the world wide web was inevitable. Putting chat rooms and interaction forums on internet sites also enabled people who were interacting with a commercial service to exchange information and commentary, and led to the development of global special interest or general interest groups, hosted by a variety of organisations.

As browser technology developed and it became easier to curate commentary, asking for content from users became more widespread, and “below the line” comments were born, inviting users to comment dynamically on content such as news sites. In contrast to Amazon’s product reviews, which were rigorously curated and therefore not dynamic, these online and “below the line” fora encouraged immediate  exchange of views. Where sites set up dedicated comments and information exchange fora, many gave birth to broad online communities, and there are today long-running informal communities associated with many news sources, with some well-known regular contributors and, as has been well documented, the rise of the internet troll and flame warrior.

exchange of views. Where sites set up dedicated comments and information exchange fora, many gave birth to broad online communities, and there are today long-running informal communities associated with many news sources, with some well-known regular contributors and, as has been well documented, the rise of the internet troll and flame warrior.

But the real communications revolution happened with the rise of the pure social platform, Facebook being the most successful to date, although many other user generated content sites such as LinkedIn, Twitter, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, etc. are also extremely popular, where the interactions and user generated content are the whole point of the site. These sites allow and encourage the development of relationships between users via a variety of tagging protocols, unrelated to validated purchases (as with Amazon reviews) or a particular subject matter interest. More than any previous forum for exchange of views, these new platforms have created alternative stars, with Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and others providing a platform for exposure for some unlikely new celebrities.

Information over social media has also started to take on a value of its own for platform prosumers, with growing respectability as more establishment and respected figures started to use it as a communications channel – in particular Twitter, which is widely employed by politicians, scientists and media figures to reach a wide audience. Forums such as Medium and Quora invite longer content on specialist subjects, changing how we perceive content and content providers, as we’ll explore below.

As the social platform has evolved, there’s also been a convergence of chat applications such as Slack, WhatsApp, WeChat and Messenger towards adopting wider and more integrated functionality, starting with file sharing and group chats and developing towards payments and other integration features, and to all extents and purposes these are now also fully fledged social platforms.

The barrier between social and marketplace platform has become more blurred over time; while social platforms have always needed to include a commercial element in the shape of advertising and behavioural data sales to maintain revenue, they are now taking on more service partners and providing more commercial opportunities to their customers, with millions of businesses represented. Payments over social media is an important milestone in this development, and with platforms now seeking banking licenses, it is clear other financial services will follow.

Ecosystem links between a wide variety of sites have increased, partially in a bid to reduce the proliferation of identities, and with the rise of the megaplatforms, now many commercial and social sites can be accessed via, and share data from, social platforms such as Facebook or Twitter. Nearly all commercial marketplace sites offer the option to share comments or content via the social platforms and some are starting to emulate more features of social platforms; the ecosystem is now in your pocket.

Circular economy platforms

As marketplace platforms emerged as a key way of how people did business, 2003 saw the birth of freecycle.com, one of a growing number of platforms dedicated to peer to peer exchange between people for no money. In some cases, as with freecycle, people simply advertise their unwanted things, so that somebody local can pick them up and make use of them instead. Others, such as LETS or the CES (Community Exchange System) are locally based trading systems that use an internal digital currency to reward people in the community for goods or services, that are exchanged peer to peer. These platforms share characteristics with locally issued physical fiat currency (such as the Brixton pound) and are generally managed based on trust and local community values.

These schemes are making use of the internet to expand the concept of circular economies in local areas. More recently, platforms have started to use web technology to exchange alternative units, to encourage green behaviours, such as the startup Bundles, which instead of selling washing machines, sells washes to consumers. This model allows an uber-like sharing economy for household appliances, reduces unnecessary usage, and also encourages manufacturers to create longer-lasting machines.

Customer uptake and behaviour

The emergence of platforms as part of our everyday lives, combined with smartphone and tablet delivery, has profoundly impacted how we interact with businesses and each other. But as well as behaviour, it’s changed our attitudes to information, privacy and identity.

Customers and marketplaces

It’s hard to think back 25 years, and many of us weren’t active retail consumers that long ago anyway, so there is a growing number of people who have never experienced anything else. The most obvious impact of platforms is our changing approach to purchasing. In the early and mid 90s, we experienced a global boom in hypermarkets, with retail stores getting larger, selling a wider variety of goods, and increasingly building on greenfield or brownfield sites out of town. In cities, large supermarkets dominated, while markets and traditional retailers were shrinking and closing their doors. Most people drove to the supermarket or hypermarket to do a weekly or fortnightly shop for groceries and household goods.

While in urban Europe most high streets would have butchers, fishmongers and greengrocers, in other countries and in rural areas, many people would have to drive to one of these, as the supermarkets encroached on traditional businesses. Clothes, books and electronic goods were bought at high street stores, which at the time were becoming increasingly dominated by a limited range of chain stores. Department stores enjoyed a healthy trade.

Many stores catered for specialist tastes, but you didn’t get variety – if you lived in a certain area, you might have access to a Chinese supermarket or even several, but other towns would have none. Specialists would exist only in larger cities, often clustered together.

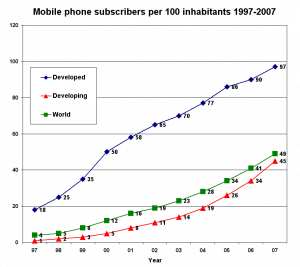

Source: Kozuch

Source: Kozuch

Mobile phones were only just becoming available and not widespread in ordinary populations, so communication between retailers and customers was by telephone or letter. While mail order was common, it was time-consuming, involving choosing items from a catalogue, waiting for the delivery, then sending back any unwanted items, via the post office.

Shops were open at limited times and almost exclusively during the daytime, so most of our shopping was done at the weekend, and particularly on a Saturday. Because of the limited range of shops available, customer stickiness was high, with customers typically visiting a small number of shops regularly for the same type of goods. Visits to city centre shopping centres or specialist stores were logistically challenging because of travel and transportation of goods, so reserved for special occasions or needs. Shopping at either was done at pre-planned times, during the day and concentrated at the weekends. Unplanned needs would see you going to a corner shop, if you had one, which opened for longer hours, but rarely overnight.

Consumer expectations of goods were consequently limited mostly by what was available easily in the same locality, or a short car journey away. While an increasingly wide variety of food was made available thanks to hypermarkets and supermarkets, your choice of books, music, furniture, clothes, electronic items and household goods was limited by what you could buy locally, or via mail order companies that you had gone to the trouble of signing up for.

Most customers also weren’t very aware of how reliable the goods they were buying were before purchasing, how they were made, or where they came from. It was hard to find independent information about customer satisfaction other than that supplied by manufacturers outside stores, where the interest was in making a sale.

Specialist shopkeepers, whether the butcher, the bookseller, the carpet salesman or specialist staff in department stores, were valuable mines of information for recommendations. Recommendations also spread through word of mouth, but primarily through the media, or through advertising, and it was becoming hard to tell the difference. The first “sex and shopping” novel, Julie Burchill’s Ambition, published in 1989, saw a pronounced increase in sales of some of the brands mentioned between the pages.

Manufacturers and retailers were also able to manage their image based on what you saw and experienced in their stores. The few ethical retailers, such as the Body Shop (now seen as a pioneer of ethical retail), were regarded as a bit fringe and possibly cranks. Nobody had a clue whether large retailers were paying taxes or employing people ethically, unless it was specifically investigated and published in the media.

Today, the high street is still holding on by its fingernails, and we do still enjoy physically visiting stores, particularly if we’re seeking expert advice, but increasingly we shop online, giving us access to an incredibly wide range of goods, inlucing subscriptions, event tickets, and services, many of which we haven’t heard of and don’t need. This has changed customer behaviour significantly:

- Buy anytime – particularly useful for busy people, now we can shop from our desks at work, while travelling, after hours or at 3 in the morning if we choose. Platforms and online shops allow us to keep adding stuff to our baskets, only paying when we check out or on delivery.

- Buy anywhere – great for those with restrictions to mobility (such as children). We can purchase on transit, at home or while away. We can order a grocery delivery for a particular time, while on the other side of the planet. And we can buy stuff from anywhere in the world.

- Buy anything – whatever you’re looking for, you’re more or less guaranteed to find it on the internet.

These aspects have made buying things much more convenient and saved us a lot of time, particularly for mundane purchases such as groceries, or specialist purchases such as sport related products or exotic ingredients, which would otherwise require a special trip. It’s also led to the more questionable benefit of:

Buy in any condition: purchasers can now buy something online while in their pyjamas, while drunk, while depressed, while sick, while fuming over a row (possibly on the internet!) or in any other state, including several that would, 25 years ago, have prevented them entering a shop. While this means that, legally, retailers have to give customers a cooling-off period, many purchasers fail to take advantage of this.

Buy in any condition: purchasers can now buy something online while in their pyjamas, while drunk, while depressed, while sick, while fuming over a row (possibly on the internet!) or in any other state, including several that would, 25 years ago, have prevented them entering a shop. While this means that, legally, retailers have to give customers a cooling-off period, many purchasers fail to take advantage of this.

And it’s changed our expectations of shopping too. Life used to be a lot simpler:

- Choice – we expect to be able to choose from a wide variety of options, either for the same type of product, such as different varieties of food produce, or different individual products, such as books or music. Although studies have demonstrated that the platformification of book and music sales has tended towards larger sales for a smaller number of titles (see Plebocracy bias for the mechanics of this), there’s also a much longer “long tail” of low-volume sales for other items.

- Price – We no longer expect a fixed price for a fixed product. Amazon has done more than any other retailer to lead us to expect lower prices, and temporary prices, while the ability to compare multiple instances of the same product with different service options, allows us to customise the service we’re buying to some degree, for example guarantee conditions, or different delivery options. Where in the past, the price of goods may have been fixed seasonally, based on popularity and trends, platforms like UBER have taken variable pricing to extremes with their dynamic surge pricing.

- Immediate delivery – Amazon has been a big part of shaping our expectations not just of instant delivery, but also of paying a premium for faster services. The impending drone deliveries will bring down delivery times even more. Other retailers and platforms were early to allow users to select delivery days and timeslots, responding to customer convenience; the UK retailer Argos was one of the earliest to offer not only same-day, but timed deliveries, at a premium.

- Buy anything – still in development, but we can now buy increasingly expensive and more significant things, alongside cheap and insignificant things, services, experiences and dreams, over platforms – with auto manufacturers now selling cars alongside platforms offering programming, custom-made t-shirts, housework, holidays, paternity tests (yep, really!), gaming and many, many more

- Information – we expect to know not just product specifications, but information about other customers’ experiences, alternative options, etc, at our fingertips.

We expect to be able to pay in a variety of ways, too, and we’re becoming increasingly reliant on electronics payments services. Many of these today are linked to our bank accounts, but it’s also possible to load money onto an increasing number of services, either through a traditional payment or using electronic money of some sort, now including digital currencies and increasingly, cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.

Customers and Information

As well as changing our purchasing behaviour and expectations, platforms have fundamentally changed our interaction with, and expectations about, information. We are now comfortable sharing personal information, and expect others to do the same, with varying degrees of openness, depending on our culture, demographic, and the type of information in question.

- The most dramatic change from a commercial perspective is in the availability of, and consumers’ willingness to share, information about products, services, and the companies that supply them; this has resulted in the need for manufacturers and service providers not only to listen to their customers, but also to curate their social profile in a completely new way.

- Of course, social platforms allow global communities to share every other type of political, social and cultural commentary they choose, and this is often associated with products, services and the companies that provide them, much more than in previous years. A company’s values become an important part of its positioning with consumers.

- This in turn, is linked to how consumers position themselves both in relation to political and social ideologies, and the extent to which they identify with companies and products associated with those ideologies. With consumer awareness, comes a growing trend to associate consumption with ideology (“lifestyle choices”) which presents both opportunities and headaches for producers.

- Of course, we’ve also seen the rise of products that are basically people – rooted in celebrity endorsement, platform celebrity now exists as a valid career choice, and people make a (sometimes very good) living out of endorsing products on the internet, encouraging people to emulate them and creating the growth of online image as a key type of social status indicator in some societies and demographics. It’s also led to the rise of social profile being more respected, and valued above, valid expertise.

- And this results in the proliferation of personal information being supplied by individuals over social and commercial platforms; personal opinions, experiences (often of products), anecdotes, photographs, trivia and other banalities. And, of course, kittens.

Key to this dynamic is the way that platform reputations are influenced and manipulated. Today’s platform reputations are shaped by opinions; these are, and will still be, open to manipulation and influence by scale, intelligent analysis and crowd dynamics such as information bubbles. We describe this in more detail in the article on Plebocracy bias.

We believe that this will be one of the areas that will see the greatest evolution in the next few years, thanks to the growing adoption of technologies such as blockchain, AI and behavioural reputation systems; while the use of data to manipulate and shape opinions is widespread today, the opportunities presented by validatable data and sophisticated behavioural analysis mean it’s now possible to create and use reputations based on facts instead of opinions. Of course, many people do, and probably will continue, to choose information that reinforces their opinion over factual information. How this evolves will shape much of how platforms and commerce interact in the future.

Businesses in the platform age

As platforms have influenced customer behaviour, so they’ve provided both opportunities and challenges for businesses. Transparency (real or perceived) is now a prerequisite, especially for larger businesses with a significant exposure to social opinions, positive or negative, and a need to curate them. Positioning in relationship to political and social attitudes is now a key part of every business strategy: today, Tribe beats Product – it’s no longer enough to produce something great, your customers have to identify with people who use your product, or with your organisation. It’s also easier for businesses to both gain and lose reputation and credibility through factors beyond their control.

The rise of the megaplatforms is problematic for other large and small businesses. In some cases, commercial platforms can leverage their scale and market value to undercut traditional players, resetting customer expectations with uncompetitively priced offerings to destroy competition, before leaving them in a monopoly position. Amazon is so strong in the book market, and is becoming a market leader in many other sectors, that it can dictate prices to primary producers and secondary sellers. Uber is openly undercutting local taxi services with the stated intention of destroying traditional providers, allowing them to reset prices as a monopoly after competition has vanished (although this strategy is having variable success).

Regulations can’t catch up with platform economics, and global platforms don’t suffer from national restrictions; their scale makes them essential to many national economies and they seem immune to traditional inconveniences suffered by smaller platforms and retailers, such as paying tax or treating workers ethically. The other side of this coin is an opportunity for labour and regulatory paradigms to shift, to both support and benefit from this new economy, but as with all market innovations, regulators struggle to catch up.

However, the opportunities are also significant. Today, businesses don’t need a global distribution network, or even advertising, if they can maintain a strong profile on social and commercial platforms through well curated consumer opinion. This means that the focus on holistic, full-stack services is now less important to strong distribution and sales, than a positive and well curated public image. Smaller businesses can achieve global footprint through creating a tribe, or building association with an existing, powerful tribe. Niche suppliers can build a global audience as scale is no longer about saturation, but cultural reach.

Conclusion

Platforms have changed the way consumers behave, how they think about products and services, how they interact with businesses and how they perceive companies, influence, celebrity, information and each other. This has significantly reshaped how businesses need to respond.

We think, however, that while significant change has already resulted from platforms, that these changes are still at the early stage of evolution. A combination of new technologies and a growing depth of generations that have always lived in the platform economy, provides the landscape for the next stage of evolution, into the ecosystem economy.

Check out hiveonline’s marketplace platform app!