2020 was bad for all of us, but what about Africa?

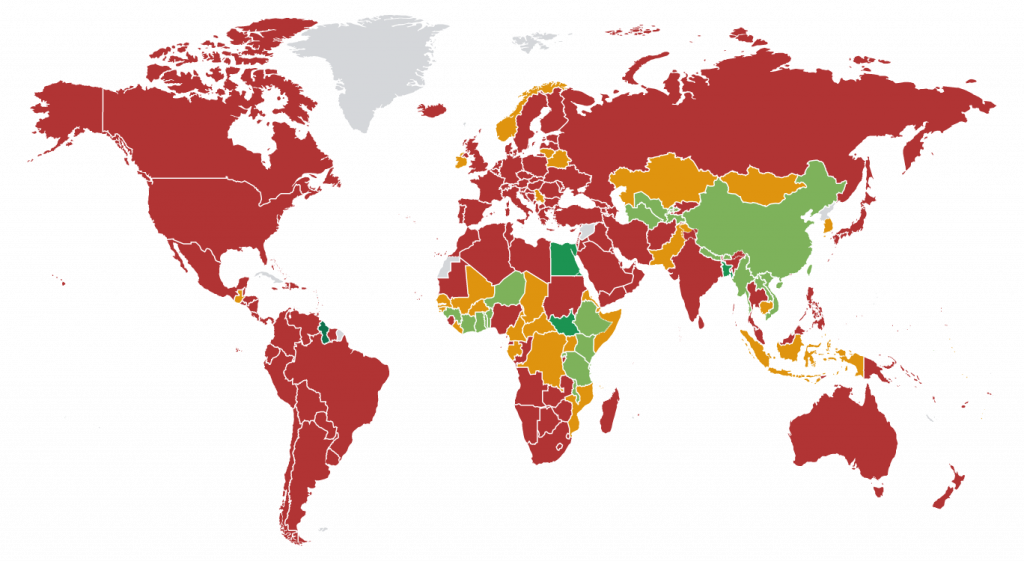

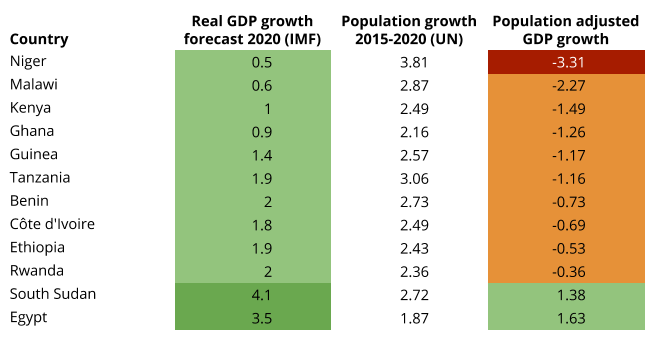

African countries, experienced at dealing with epidemics and lacking satisfactory healthcare systems, have taken robust measures against COVID-19 and so have mostly been relatively successful in controlling the spread of the virus, but the economic impact has been severe. The fallout has reversed previous 2020 growth forecasts of 3.9% to a predicted average growth of between -1.7 percent in the best case scenario and -3.4 percent in the worst. Southern Africa, which includes South Africa, the worst-hit country on the continent with over a million cases of COVID-19, is the region with the worst outlook, at between -4.9% and -6.6%. From a raw GDP growth perspective, however, it doesn’t look too bad in global terms.

2020 Growth Forecast by Country

But Africa is home to most of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs); nearly half of the continent’s countries have a GDP per capita of less than USD 1,000, with the fastest growing population. For countries starting from such a low base, economic growth is a necessity. They are also some of the countries most affected by the impact of climate change, while another impact of economic contraction is the increase in internecine conflict and insurgency in the Sahel and other regions.

Africa’s economy is dependent on the rest of the world — nearly 50% of 2020’s previously forecast growth was in investment, while export of commodities and tourism are both important economic drivers. Commodity prices plummeted in 2020 and although many have recovered lately, oil and agricultural prices remain below forecast, impacting most African countries. Interrupted logistics for transporting fresh goods created insurmountable barriers; Kenya’s flower industry, worth over $1 billion, was brought to a standstill, while tourism, responsible for over 15% of Rwanda’s GDP in 2019, stalled.

Chinese investment has been an important economic driver but is now slowing, as Chinese economic growth has slowed and African countries struggle to repay debts. They’ve also been hit by the recession in developed countries — Nigeria received over $23.8 billion in remittances from diaspora last year, a figure that will drop by 23.1% this year, as immigrants to richer countries are disproportionately likely to have lost jobs due to the crisis. Border restrictions have also impacted labour mobility and cross-border trade.

Agriculture has a hundred times more informal than formal businesses

And GDP doesn’t tell the whole story; much of Africa’s commerce (between 25% of GDP in South Africa and up to 65% elsewhere) is informal and undocumented, which makes it hard to measure. Many countries’ economies are largely driven by agricultural employment, a sector that has a hundred times more informal than formal businesses in some countries, while informal businesses outweigh formal businesses by 10 to 1 across industries.

At a local level, restrictions on movement have reduced markets and led to price inflation and scarcity of food in some countries, already struggling with logistics and inefficient markets. It’s disrupted community activity such as markets and savings groups, preventing people meeting in numbers. African communities are finding creative solutions, relying on strong social bonds to manage supply chains and delivery services, leaning further on informal, unpaid work, with the burden disproportionately falling on women.

African leaders are encouraging lenders and mobile money providers to reduce costs and provide additional capital to small businesses, however lenders are themselves facing challenges with more defaults, so the stimulus has limited impact and hasn’t reached small scale producers. And while international bodies and governments have agreed to postpone repayments on African countries’ debts, many Chinese lenders, who own the lion’s share of bilateral debt to Africa, are not complying. Zambia has now become the first country to default in the COVID crisis.

So what’s the answer? Shrinking or reduced growth economies won’t encourage foreign investment, and defaulting on lending will reduce countries’ access to affordable capital. But African markets need foreign stimulus to grow.

The problem is multi-layered, and while it’s been exposed further by COVID, inefficiencies in African markets and weaknesses in financial systems have always hurt small producers. Capital is hard to access and astronomically priced, while domestic market access can be just as challenging as export. The cash economy, with deep layers of intermediaries, keeps primary producers poor and doesn’t give much upside to others — very few people in the rural economy can afford good education for their children or access to high quality healthcare, or to use their land effectively for improved yields, and so the problems are passed on generationally.

Can technology help?

Digital solutions have shown the potential to transform access to work and to critical financial services, starting with M-Pesa, which increased Kenyan’s access to financial services from just 17% to over 90% in less than a decade. However, without market growth, access to payments and lending doesn’t help the economy as a whole; businesses which were able to start thanks to M-Pesa entered crowded and inefficient markets, while Uber’s drivers are facing bankruptcy and eviction because they took out auto loans to serve a market that’s collapsed.

Multi-layered challenges need holistic solutions and collaborative interventions which address capital and market access:

- financial interventions to improve agricultural outputs and access to financial services;

- structured lending to pass on lower capital costs and access to agricultural inputs, helping farmers and their communities to increase productivity;

- digitising harvest data with predictive analytics to improve market access, so communities can generate wealth more efficiently

Communities which can afford it, invest in better infrastructure, education and healthcare, benefiting the next generation while creating jobs and escaping the poverty trap.

Farmers are forced to choose between food and sending the kids to school, or increasing their yield

The cashew farmers we’re working with in Mozambique are facing all these problems — they can’t afford crop care or new saplings to increase productivity, but their trees are aging, so yields are declining. They earn between 70–120 USD for a crop, and while they’re also growing other crops, they’re forced to choose between food and sending the kids to school, or increasing their yield and their income — which could double with the right crop care. They’re accepting low prices from middle men who will take their crop on the spot, rather than waiting for Cooperatives to give them a better price, but weeks later. The processors aren’t able to help them, because the global market for cashews hit challenges over the Summer, so their cost of capital is high too.

With the right data, Cooperatives can play a pivotal role in creating efficient markets and, like savings groups, in managing simple lending, but their control of data is weak, and it’s impossible to trace a farmer between paper systems and spreadsheets.

That’s why our myCoop.online platform first helps Cooperatives identify farmers, measuring forecast and actual yields, giving them a clear confidence indicator for financial institutions and buyers.

This year we’re introducing structured lending, so Coops can help farmers manage agricultural inputs and increase yields, without those difficult choices. As we engage the full value chain, we’ll help processors reduce capital costs.

It’s also important for governments and other agencies to be able to distribute tailored vouchers, for example through vsla.online and myCoop.online, and for cooperatives to link quality of crops to the agricultural interventions that the lending supports — eventually allowing for a virtuous cycle of certification and access to premium markets.

It’s amazing to see how much difference digital data makes to efficiency and market access — even with crop prices temporarily depressed, increasing yields can compensate and help farmers to build financial resilience. Our analytics detect people trying to game the system, and because the data’s written to the blockchain, it can’t be tampered with. Digitising can increase efficiencies in lending, driving down the cost of borrowing, through reputation scoring, which gives lenders confidence in communities and farmers, and then through blockchain enabled mobile money, which can pass on lower costs of capital between actors in the value chain and support micropayments.

It takes a village — a financial technology solution is just one component

All of this takes a village — we firmly believe that a financial technology solution, while pivotal, is just one component to addressing multi-layered problems. So in Mozambique, we’re working with AMPCM, the Mozambican Association of Modern Cooperatives, Norwegian NGO Norges Vel, the Mozambican Nut Association IAM, International NGO consultancy Technoserve, local banks and others, to help these communities build resilience. And that’s just one example — there is a growing community of technology and other social enterprise companies who have recognised the opportunity to help Africa become more prosperous, working with NGOs and Civil Society organisations.

We’re about to kick off some new projects in two new countries, and our experience has shown that while the needs we’re addressing are common to all, each community’s experience is different, so we’re providing locally tailored solutions based on standard services. With these holistic solutions and the partnerships we’re building, along with the growing number of other enterprises in this space, we’re helping communities through the current crisis, to build resilience, prosperity and sustainability for their own and future generations.